The original Korean version of this update was posted on April 3, 2025. (Click here to view.)

On March 29th, ten participants gathered in an hybrid seminar to engage in a discussion following a reading of articles by Hyunsoog So and Clara Hyun-Jung Lee. 1. So, Hyunsoog (2018). “Postwar History of War Orphans in the 1950s: Their Condition and Social Measures.” Journal of Korean Modern and Contemporary History, vol. 84. ■ Summary

Following the Korean War, orphans in South Korean society were primarily absorbed into systems of international adoption and institutional care. However, these institutions suffered from operational instability from excessive reliance on foreign funding and managerial corruption. As a result, many orphans were either neglected in substandard conditions or driven into vagrancy on the streets. These orphaned vagrants were regarded as potential criminals and became easy targets for indiscriminate police screening and arrest. In the late 1950s, American psychological and psychiatric theories were introduced to South Korea. Within this framework, a reductionist view took hold, interpreting the perceived delinquent tendencies of orphans not as a product of social conditions but as stemming from individual predispositions. This perspective contributed to their social exclusion and reinforced stigmatization. ▶ Discussion - Just as ‘vagrants’ were perceived as potential criminals, orphans were viewed through a lens of sympathy that, in effect, served as a mechanism of differentiation and discrimination. Moreover, operational corruption within care facilities persists even today. It is therefore crucial to examine the structural issues operating beneath the surface of child welfare and child protection systems.

- Did the social milieu at the time believe that making children in need of protection invisible would constitute a solution to the problem? By excluding these children from the category of “citizen” and attempting to resolve the issue swiftly through international adoption, the foundations were laid for the recently revealed cases of document manipulation and inadequate record-keeping in international adoption practices.

- Although the Korean War ended in 1953, it was during the 1970s, marked by rapid industrialization and urbanization, that the number of children placed in childcare shelters surged. This suggests that it was capitalism, rather than war, that more profoundly contributed to the separation of children from their families.

- Other similar cases deserve attention. In the early 1960s, the Seosan Pioneering Group was formed, composed of orphans and vagrants who were forcibly sent to undeveloped lands to clear and reclaim them. Some were even relocated to rural farms in Paraguay. Records also indicate that older orphaned girls were selectively sent to Germany to work as general laborers in hospitals. Little to no follow-up reporting exists on what became of them. It is haunting to consider how many may have actually survived.

- The introduction of American psychology and psychiatry also contributed to the stigmatization of unwed mothers in South Korea. During the 1950s and 1960s, social welfare discourse, heavily influenced by Freudian psychoanalysis, tended to pathologize unwed motherhood. Psychoanalytic explanations framed unwed mothers as individuals who became pregnant either to test their sexual capabilities or as an act of rebellion against repressive parental authority.

- The experiences of girl orphans were often rendered invisible. While some have interpreted their absorption into households as domestic workers, such as maids, as a form of care or protection, this view fails to acknowledge the exploitative nature of these arrangements. Unlike boys, who within exploitative systems had at least some opportunity to navigate survival, whether as the exploited or the exploiter, girls placed in private homes were denied even that limited agency. Figures such as the “Western princesses” and mixed-race children have slowly begun to re-enter the historical narrative. However, many girl orphans absorbed into the private sphere remain largely erased, their lives obscured and forgotten.

■ Summary

This article draws on interviews with birth mothers who sent their children for international adoption in the mid-20th century, examining the hojuje (head-of-household) system as both a legal institution and a sociocultural norm that constrained their agency as mothers. Under a collective perception that defined the hojuje-based family as the normative household structure, various actors such as the government, adoption agencies, childcare institution staff, and family members functioned as mediators of these norms and exerted broad influence over birth mothers’ decisions to relinquish their right to raise their children. In order to ensure that the individual rights of birth mothers and of those affected by international adoption are protected, appropriate legal reforms must be enacted. Furthermore, these legal changes should serve as the foundation for reshaping social and cultural norms, thereby expanding individual perceptions and practices. Only under such conditions can diverse forms of family be more broadly recognized, accepted, and welcomed by society. ▶ Discussion - The article should clearly define the terms "disclosed adoption"(gonggae ipyang), "undisclosed adoption"(bigonggae ipyang), and "open adoption"(gaebang ipyang). The terms gonggae ipyang and bigonggae ipyang refer to whether the adoptee is informed of their adoption status. In contrast, gaebang ipyang pertains to whether the adoptive family maintains a relationship or connection with the birth parents. Some European countries have implemented forms of adoption that align more closely with what is referred to as gaebang ipyang.

- The topic of international adoption requires an investigation into the global order and historical context of the time. Attributing its causes primarily to South Korea’s patriarchy or developmental belatedness reflects an external, Western-oriented perspective. It is regrettable that the article addressed this complex and reciprocal issue primarily through the lens of individual identity.

- It is limiting that the article identifies the hojuje (head-of-household system) as the sole factor influencing the decision to relinquish children for international adoption. Class dynamics also operated within the framework of the Confucian hojuje. For example, economically capable male heads of household would sometimes register and raise children born out of wedlock. They also maintained proper respect toward the birth mother, referred to in Korean as chulmo (a divorced mother). In contrast, male heads of household without sufficient economic means generally did not. Rather, it was the modern patriarchy, based on exclusive monogamy, that made it more likely that out-of-wedlock children would not be included in their birth families and would be adopted into unrelated families.

- One of the strengths of this study lies in its rich and well-conducted interview data, which demonstrates strong methodological integrity as a qualitative research project. However, the analysis is limited by its simplification of variables and its omission of the adoptees’ experiences following reunification with their birth families.

- It is necessary to consider the broader network of factors, including adoptive parents, population control within the project of modern nation-building and the influence of demands from the United States.

- The recommendation that "legal reform can lead to changes in individual perception" risks reflecting a structural determinism, rather than recognizing the dynamic interaction between institutional systems and individual agency. Such a view overlooks the extent to which legal changes, such as the abolition of the hojuje or revisions to adoption-related laws, have been driven by the accumulated shifts in personal and collective consciousness.

- It is also striking that, even in cases involving pregnancies resulting from rape or sexual violence, some birth mothers expressed a desire to raise their children. This highlights the urgent need to establish institutional conditions that enable all individuals to live with dignity, regardless of circumstance.

Building on last month’s discussions on "social work during the Japanese colonial period" and "the normativity of the modern family," this session offered a meaningful opportunity to reflect on how various social factors influence individual lives, particularly through the experiences of orphans in the postwar period and birth mothers who sent their children for international adoption. Many thanks to the presenters and participants for their thoughtful contributions. It was a pleasure and a privilege to study together with all of you. Looking forward to seeing everyone again next month! The UMI4AA seminar is open to everyone.

- Registration Fee: KRW 5,000 per session

- Payment Info: Hana Bank 563-910001-36804 | Unwed Mothers Initiative for Archiving and Advocacy

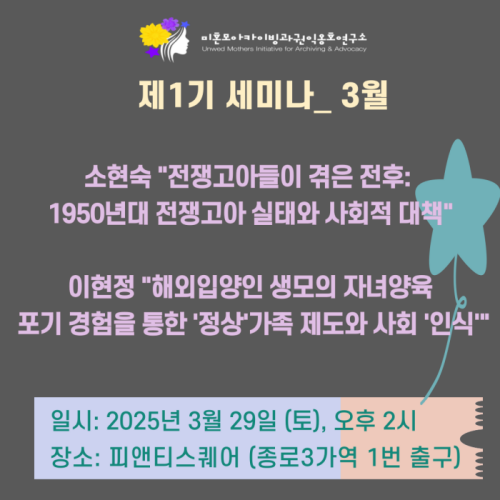

■ March Seminar Announcement

Lee, Sookjin (2022). “The Making of ‘Normal Family’ in Korean Protestantism: Focused on the Strategy of Otherization and Subjectification.” Studies in Religion (The Journal of the Korean Association for the History of Religions), vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 87–112. Oh, Arissa H. (2019). “A New Kind of Missionary Work: Christians, Christian Americanists, and the Adoption of Korean GI Babies, 1955–1961.” To Save the Children of Korea: The Cold War Origins of International Adoption. Translated by Eun-Jin Lee. KoRoot. Published in Korean as Wae geu aideureun hangugeul tteonaji aneul su eopseotna: Haeoeeabyangui sumgyeojin yeoksa (unofficial English translation: Why Those Children Couldn’t Help but Leave Korea: The Hidden History of Overseas Adoption). ▶ UMI4AA 1st Seminar Series Sign Up: Click HERE to register for the next session. |